Giovanni Bellini

Giovanni Bellini

53 artworks

Italian painter and musician

Born 1430 - Died 1516

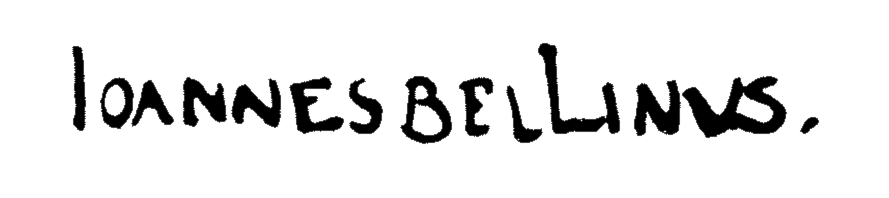

{"Id":290,"Name":"Giovanni Bellini","Biography":"\u003Cstrong\u003EGIOVANNI BELLINI\u003C/strong\u003E (1430-1516) is generally assumed to have been the second son of \u003Ca href=\u0022/asp/database/art.asp?aid=304\u0022 target=\u0022_blank\u0022 class=\u0022link\u0022\u003EJacopo\u003C/a\u003E by his wife Anna; though the fact that she does net mention him in her will with her other sons has thrown some slight doubt upon the matter. At any rate he was brought up in his fathers house, and always lived and worked in the closest fraternal relation with \u003Ca href=\u0022/asp/database/art.asp?aid=289\u0022 target=\u0022_blank\u0022 class=\u0022link\u0022\u003EGentile\u003C/a\u003E. Up till the age of nearly thirty we find documentary evidence of the two sons having served as their fathers assistants in works both at Venice and Padua. In Giovanni\u0027s earliest independent works we find him more strongly influenced by the harsh and searching manner of the Paduan school, and especially of his own brother-in-law \u003Ca href=\u0022/asp/database/art.asp?aid=785\u0022 target=\u0022_blank\u0022 class=\u0022link\u0022\u003EMantegna\u003C/a\u003E, than by the more graceful and facile style of Jacopo. This influence seems to have lasted at full strength until after the departure of his brother-in-law Mantegna for the court of Mantua, in 1460. The earliest of Giovanni\u0027s independent works no doubt date from before this period. Three of these exist at the Correr museum in Venice: a \u003Cu\u003ECrucifixion\u003C/u\u003E, a \u003Cu\u003ETransfiguration\u003C/u\u003E, and a \u003Cu\u003EDead Christ supported by Angels\u003C/u\u003E. Two Madonnas of the same or even earlier date are in private collections in America, a third in that of Signor Frizzoni at Milan; while two beautiful works in the \u003Ca href=\u0022http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/\u0022 target=\u0022_blank\u0022 class=\u0022link\u0022\u003ENational Gallery\u003C/a\u003E of London seem to bring the period to a close. One of these is of a rare subject, the \u003Cu\u003EBlood of the Redeemer\u003C/u\u003E; the other is the fine picture of \u003Cu\u003EChrist\u0027s Agony in the Garden\u003C/u\u003E, formerly in the Northbrook collection. The last-named piece was evidently executed in friendly rivalry with Mantegna, whose version of the subject hangs near by; the main idea of the composition in both cases being taken from a drawing by Jacopo Bellini in the \u003Ca href=\u0022http://www.thebritishmuseum.ac.uk/\u0022 target=\u0022_blank\u0022 class=\u0022link\u0022\u003EBritish Museum\u003C/a\u003E sketch-book. In all these pictures Giovanni combines with the Paduan severity of drawing and complex rigidity of drapery a depth of religious feeling and human pathos which is his own. They are all executed in the old tempera method; and in the last named the tragedy of the scene is softened by a new and beautiful effect of romantic sunrise color. In a somewhat changed and more personal manner, with less harshness of contour and a broader treatment of forms and draperies, but not less force of religious feeling, are the two pictures of the \u003Cu\u003EDead Christ supported by Angels\u003C/u\u003E, in these days one of the masters most frequent themes, at Rimini and at Berlin. Chronologically to be placed with these are two Madonnas, one at the church of the \u003Ca href=\u0022http://www.veniceinperil.org.uk/pastproj/cannaregio.html\u0022 target=\u0022_blank\u0022 class=\u0022link\u0022\u003EMadonna del Orto\u003C/a\u003E at Venice and one in the Lochis collection at Bergamo; devout intensity of feeling and rich solemnity of color being in the case of all these early Madonnas combined with a singularly direct rendering of the natural movements and attitudes of children.\u003Cbr\u003E\u003Cbr\u003EThe above-named works, all still executed in tempera, are no doubt earlier than the date of Giovanni\u0027s first appointment to work along with his brother and other artists in the Scuola di San Marco, where among other subjects he was commissioned in 1470 to paint a \u003Cu\u003EDeluge with Noah\u0027s Ark\u003C/u\u003E. None of the masters works of this kind, whether painted for the various schools or confraternities or for the ducal palace, have survived. To the decade following 1470 must probably be assigned a \u003Cu\u003ETransfiguration\u003C/u\u003E now in the Naples museum, repeating with greatly ripened powers and in a much screner spirit the subject of his early effort at Venice; and also the great altar-piece of the \u003Cu\u003ECoronation of the Virgin\u003C/u\u003E at Pesaro, which would seem to be his earliest effort in a_form of art previously almost monopolized in Venice by the \u003Ca href=\u0022http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/15491b.htm\u0022 target=\u0022_blank\u0022 class=\u0022link\u0022\u003Erival school of the Vivarini\u003C/a\u003E. Probably not much later was the still more famous altar-piece painted in tempera for a chapel in the church of S. Giovanni e Paolo, where it perished along with \u003Ca href=\u0022/asp/database/art.asp?aid=125\u0022 target=\u0022_blank\u0022 class=\u0022link\u0022\u003ETitian\u0027s\u003C/a\u003E \u003Cu\u003EPeter Martyr\u003C/u\u003E and \u003Ca href=\u0022/asp/database/art.asp?aid=573\u0022 target=\u0022_blank\u0022 class=\u0022link\u0022\u003ETintoretto\u0027s\u003C/a\u003E \u003Cu\u003ECrucifixion\u003C/u\u003E in the disastrous fire of 1867. After 1479-1480 very much of Giovanni\u0027s time and energy must have been taken up by his duties as conservator of the paintings in the great hall of the ducal palace, in payment for which he was awarded, first the reversion of a broker\u0027s place in the \u003Ca href=\u0022http://www.venicebanana.com/eng/ar010.htm\u0022 target=\u0022_blank\u0022 class=\u0022link\u0022\u003EFondaco dei Tedeschi\u003C/a\u003E, and afterwards, as a substitute, a fixed annual pension of eighty ducats. Besides repairing and renewing the works of his predecessors he was commissioned to paint a number of new subjects, six or seven in all, in further illustration of the part played by Venice in the wars of \u003Ca href=\u0022http://www.bartleby.com/65/ba/Barbaros.html\u0022 target=\u0022_blank\u0022 class=\u0022link\u0022\u003EBarbarossa\u003C/a\u003E and the pope. These works, executed with much interruption and delay, were the object of universal admiration while they lasted, but not a trace of them survived the fire of 1577; neither have any other examples of his historical and processional compositions come down, enabling us to compare his manner in such subjects with that of his brother \u003Ca href=\u0022/asp/database/art.asp?aid=289\u0022 target=\u0022_blank\u0022 class=\u0022link\u0022\u003EGentile\u003C/a\u003E. Of the other, the religious class of his work, including both altar-pieces with many figures and simple Madonnas, a considerable number have fortunately been preserved. They show him gradually throwing off the last restraints of the 15th-century manner; gradually acquiring a complete mastery of the new oil medium introduced in Venice by \u003Ca href=\u0022http://www.artcyclopedia.com/artists/antonello_da_messina.html\u0022 target=\u0022_blank\u0022 class=\u0022link\u0022\u003EAntonello da Messina\u003C/a\u003E about 1473, and mastering with its help all, or nearly all, the secrets of the perfect fusion of colors and atmospheric gradation of tones. The old intensity of pathetic and devout feeling gradually fades away and gives place to a noble, if more worldly, serenity and charm. The enthroned Virgin and Child become tranquil and commanding in their sweetness; the personages of the attendant saints gain in power, presence and individuality; enchanting groups of singing and viol-playing angels symbolize and complete the harmony of the scene. The full splendour of Venetian color invests alike the figures, their architectural framework, the landscape and the sky. The altar-piece of the Fran at Venice, the altar-piece of San Giobbe, now at the academy, the \u003Cu\u003EVirgin between SS. Paul and George\u003C/u\u003E, also at the academy, and the altarpiece with the kneeling \u003Ca href=\u0022http://www.nationmaster.com/encyclopedia/Doges-of-Venice\u0022 target=\u0022_blank\u0022 class=\u0022link\u0022\u003Edoge\u003C/a\u003E Barbarigo at Murano, are a~nong the most conspicuous examples. Simple Madonnas of the same period (about 1485-1490) are in the Venice academy, in the National Gallery, at Turin and at Bergamo. An interval of some years, no doubt chieHy occupied with work in the Hall of the Great Council, seems to separate the last-named altar-pieces from that of the church of San Zaccaria at Venice, which is perhaps the most beautiful and imposing of all, and is dated 1505, the year following that of Giorgione\u0027s \u003Cu\u003EMadonna\u003C/u\u003E at Castelfranco. Another great altar-piece with saints, that of the church of San Francesco de la Vigna at Venice, belongs to 1507; that of \u003Cu\u003ELa Corona\u003C/u\u003E at Vicenza, a \u003Cu\u003EBaptism of Christ\u003C/u\u003E in a landscape, to 1510; to 1513 that of San Giovanni Crisostomo at Venice, where the aged saint Jerome, seated on a hill, is raised high against a resplendent sunset background, with SS. Christopher and Augustine standing facing each other below him, in front. Of Giovanni\u0027s activity in the interval between the altar-pieces of San Giobbe and of Murano and that of San Zaccania, there are a few minor evidences left, though the great mass of its results perished with the fire of the ducal palace in 1577. The examples that remain consist of one very interesting and beautiful allegorical picture in the \u003Ca href=\u0022http://www.uffizi.firenze.it/\u0022 target=\u0022_blank\u0022 class=\u0022link\u0022\u003EUffizi\u003C/a\u003E at Florence, the subject of which had remained a riddle until it was recently identified as an illustration of a French medieval allegory, the \u003Cu\u003EP\u0026egrave;lerinage de la Vie Humaine\u003C/u\u003E by Guillaume de Guilleville; with a set of five other allegories or moral emblems, on a smaller scale and very romantically treated, in the academy at Venice. To these should probably be added, as painted towards the year 1505, the portrait of the doge Loredano in the National Gallery, the only portrait by the master which has been preserved, and in its own manner one of the most masterly in the whole range of painting.\u003Cbr\u003E\u003Cbr\u003EThe last ten or twelve years of the masters life saw him besieged with more commissions than he could well complete. Already in the years 1501-1504 the marchioness \u003Ca href=\u0022http://www.encyclopedia4u.com/i/isabella-d-este.html\u0022 target=\u0022_blank\u0022 class=\u0022link\u0022\u003EIsabella Gonzaga\u003C/a\u003E of Mantua had had great difficulty in obtaining delivery from him of a picture of the \u003Cu\u003EMadonna and Saints\u003C/u\u003E (now lost) for which part payment had been made in advance. In 1505 she endeavoured through \u003Ca href=\u0022http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02425e.htm\u0022 target=\u0022_blank\u0022 class=\u0022link\u0022\u003ECardinal Bembo\u003C/a\u003E to obtain from him another picture, this time of a secular or mythological character. What the subject of this piece was, or whether it was actually delivered, we do not know. \u003Ca href=\u0022/asp/database/art.asp?aid=122\u0022 target=\u0022_blank\u0022 class=\u0022link\u0022\u003EAlbrecht D\u0026uuml;rer\u003C/a\u003E, visiting Venice for a second time in 1506, reports of Giovanni Bellini as still the best painter in the city, and as full of all courtesy and generosity towards foreign brethren of the brush. In 1507 Gentile Bellini died, and Giovanni completed the picture of the \u003Cu\u003EPreaching of St Mark\u003C/u\u003E which he had left unfinished; a task on the fulfilment of which the bequest by the elder brother to the younger of their father\u0027s sketch-book had been made conditional. In 1513 Giovanni\u0027s position as sole master (since the death of his brother and of Alvise Vivarini) in charge of the paintings in the Hall of the Great Council was threatened by an application on the part of his own former pupil, Titian, for a joint-share in the same undertaking, to be paid for on the same terms. Titian\u0027s application was first granted, then after a year rescinded, and then after another year or two granted again; and the aged master must no doubt have undergone some annoyance from his sometime pupil\u0027s proceedings. In 1514 Giovanni undertook to paint a \u003Cu\u003EBacchanal\u003C/u\u003E for the \u003Ca href=\u0022http://webexhibits.org/feast/context/alfonso.html\u0022 target=\u0022_blank\u0022 class=\u0022link\u0022\u003Eduke Alfonso of Ferrara\u003C/a\u003E, but died in 1516, leaving it to be finished by his pupils; this picture is now at Alnwick.\u003Cbr\u003E\u003Cbr\u003EBoth in the artistic and in the worldly sense, the career of Giovanni Bellini was upon the whole the most serenely and unbrokenly prosperous, from youth to extreme old age, which fell to the lot of any artist of the early Renaissance. He lived to see his own school far outshine that of his rivals, the Vivarini of Murano; he embodied, with ever growing and maturing power, all the devotional gravity and much also of the worldly splendour of the Venice of his time; and he saw his influence propagated by a host of pupils, two of whom at least, Giorgione and Titian, surpassed their master. Giorgione he outlived by five years; Titian, as we have seen, challenged an equal place beside his teacher. Among the best known of his other pupils were, in his earlier time, \u003Ca href=\u0022http://www.artcyclopedia.com/artists/previtali_andrea.html\u0022 target=\u0022_blank\u0022 class=\u0022link\u0022\u003EAndrea Previtali\u003C/a\u003E, \u003Ca href=\u0022http://www.artcyclopedia.com/artists/conegliano_giambattista_cima_da.html\u0022 target=\u0022_blank\u0022 class=\u0022link\u0022\u003ECima da Conegliano\u003C/a\u003E, \u003Ca href=\u0022http://www.artcyclopedia.com/artists/basaiti_marco.html\u0022 target=\u0022_blank\u0022 class=\u0022link\u0022\u003EMarco Basaiti\u003C/a\u003E, \u003Ca href=\u0022http://wwar.com/masters/r/rondinelli-niccolo.html\u0022 target=\u0022_blank\u0022 class=\u0022link\u0022\u003ENiccolo Rondinalli\u003C/a\u003E, Piermaria Pennacchi, \u003Ca href=\u0022http://wwar.com/masters/p/pellegrino_da_san_daniele.html\u0022 target=\u0022_blank\u0022 class=\u0022link\u0022\u003EMartino da Udine\u003C/a\u003E, \u003Ca href=\u0022http://www.artcyclopedia.com/artists/mocetto_girolamo.html\u0022 target=\u0022_blank\u0022 class=\u0022link\u0022\u003EGirolamo Mocetto\u003C/a\u003E; in later time, \u003Ca href=\u0022http://www.artcyclopedia.com/artists/bissolo_pier_francesco.html\u0022 target=\u0022_blank\u0022 class=\u0022link\u0022\u003EPierfrancesco Bissolo\u003C/a\u003E, \u003Ca href=\u0022http://www.artcyclopedia.com/artists/vincenzo_di_catena.html\u0022 target=\u0022_blank\u0022 class=\u0022link\u0022\u003EVincenzo Catena\u003C/a\u003E, \u003Ca href=\u0022/asp/database/art.asp?aid=819\u0022 target=\u0022_blank\u0022 class=\u0022link\u0022\u003ELorenzo Lotto\u003C/a\u003E and \u003Ca href=\u0022/asp/database/art.asp?aid=2074\u0022 target=\u0022_blank\u0022 class=\u0022link\u0022\u003ESebastian del Piombo\u003C/a\u003E.\u003Cbr\u003E\u003Cbr\u003EBIBLIOGRAPHY. Vasari, ed. Milanesi, vol. iii.; Ridolfi, \u003Cu\u003ELe Maraviglie\u003C/u\u003E, \u0026c., vol. i.; Francesco Sansovino, \u003Cu\u003EVenezia Descritta\u003C/u\u003E; Morelli, \u003Cu\u003ENotizia, \u0026c., di un Anonimo\u003C/u\u003E; Zanetti, \u003Cu\u003EPittura Veneziana\u003C/u\u003E; F. Aglietti, \u003Cu\u003EElogio Storico di Jacopo e Giovanni Bellini\u003C/u\u003E; G. Bernasconi, \u003Cu\u003EGenni intorno Ia vita e fe opere di Jacopo Bellini\u003C/u\u003E; Moschini, \u003Cu\u003EGiovanni Bellini e pittori contemporanei\u003C/u\u003E; E. Galichon in \u003Cu\u003EGazette des Beaux-Arts\u003C/u\u003E (i866); Crowe and \u003Ca href=\u0022http://www.whistler.arts.gla.ac.uk/biog/Caval_G.htm\u0022 target=\u0022_blank\u0022 class=\u0022link\u0022\u003ECavalcaselle\u003C/a\u003E, \u003Cu\u003EHistory of Painting in North Italy\u003C/u\u003E, vol. i.; Hubert Janitschek, \u003Cu\u003EGiovanni Bellini in Dohmes Kunst und K\u0026uuml;nstler\u003C/u\u003E; Julius Meyer in \u003Cu\u003EMeyers Allgemeines K\u0026uuml;nstler-Lexileon\u003C/u\u003E, vol. iii. (1885); Pompco Molmenti, \u003Cu\u003EI pittori Bellini in Studi e ricerche di Storia d\u0027Arte\u003C/u\u003E; P. Paoletti, \u003Cu\u003ERaccolta di documenti inedsti\u003C/u\u003E, fasc. i.; Vasari, \u003Cu\u003EVile di Gentile da Fabriano e Vittor Pisanello\u003C/u\u003E, ed. Venturi; Corrado Ricci in \u003Cu\u003ERassegna d\u0027Arte\u003C/u\u003E (1901, 903), and \u003Cu\u003ERivista d\u0027Arte\u003C/u\u003E (1906); Roger Fry, Giovanni Bellini in \u003Cu\u003EThe Artists Library\u003C/u\u003E; Everard Meyncil, Giovanni Bellini in \u003Cu\u003ENewness Art Library\u003C/u\u003E (useful for a nearly complete set of reproductions of the known paintings); Corrado Ricci, \u003Cu\u003EJacopo Bellini e i suoi Libri di Disegni\u003C/u\u003E; Victor Goloubeff, \u003Cu\u003ELes Dessins de Jacopo Bellini\u003C/u\u003E (the two works last cited reproduce in full, that of M. Goioubeff by far the most skilfully, the contents of both the Paris and the London sketch-books). (S.C.)\u003Cbr\u003E\u003Cbr\u003E\u003Cstrong\u003E\u003Cu\u003ESource:\u003C/u\u003E\u003C/strong\u003E Entry on the artist in the \u003Ca href=\u0022http://92.1911encyclopedia.org/B/BE/BELLINI.htm\u0022 target=\u0022_blank\u0022\u003E1911 Edition Encyclopedia\u003C/a\u003E.\u003Cp\u003E","BiographicalImageUrl":null,"StartYear":1430,"EndYear":1516,"Awards":null,"HasAlbums":false,"HasPortraits":true,"HasRelationships":true,"HasArticles":false,"HasDepictedPlaces":false,"HasLetters":false,"HasLibraryItems":false,"HasProducts":true,"HasSignatures":true,"HasVideos":false,"HasMapLocations":true,"TotalArtworks":53}