P.A.J. Dagnan-Bouveret and the Illusion of Photographic Naturalism

When the following essay appeared in Arts Magazine (April, 1982) on the work and contribution of Pascal Adolphe Jean Dagnan - Bouveret (1852-1929) it represented a concerted effort to reveal the ways in which Dagnan-Bouveret had made significant changes to the evolution of naturalist painting and, by implication, to the academic tradition of which he was then considered a primary proponent.

Bouveret's paintings has continued, not only with further study of his naturalist imagery, but with a renewed interest in his later symbolist-religious compositions and his role in expanding portraiture during the Third Republic in France. In each of these instances, as we have gained a broader picture of the renewal of academic creativity, the position of Dagnan-Bouveret has loomed as dramatically significant. As an elected member to the Institut de France, as a replacement following the death of the still life painter Antoine Vollon in 1900, Dagnan-Bouveret became, by the time of his death, a staunch opponent of modernism and an avowed continuator of the opinions, traditions and direction of his mentor, Jean-Léon Gérôme . In effect, Dagnan-Bouveret, became an arch anti-modernist, was recognized as such at the time, as well as a proponent for the support of the entire academic tradition at the moment when it was coming under its fiercest attack from the modernist abstractionists.

Now, eighteen years after the appearance of the Arts Magazine article, Dagnan-Bouveret is about to become the focus of a major international exhibition that will open at the Dahesh Museum (Fall, 2002). The strains of his work that we first identified in 1982 — his interest in reconceptualizing contemporary scene painting, his photographic verisimilitude, Dagnan's ability to create new working methods both in drawings and paintings — have contributed to his growing deftness as a major late proponent of the revivified academic tradition. But Dagnan-Bouveret was more than this. He was capable of creating large-scale paintings that gave the impression of a "virtual reality", while, at heart, they were constructions that he had developed, enlarged, pursued in the quiet of his own studio. Dagnan-Bouveret's work reference a magical ability to understand the significance of new technology and how new approaches could develop a heightened range of creative possibilities, if they could be mastered by a painter with skill and creative imagination.

In making this article available once again to a large audience, we are further demonstrating Dagnan-Bouveret's importance to our era and preparing a continued foundation for acknowledging this in the exhibition "Dagnan-Bouveret and the Academic Tradition" in 2002.

That Pascal Adolphe Jean Dagnan-Bouveret relied heavily on photography for the creation of his paintings may represent not only the practice of one naturalist artist but may suggest that other painters of realism employed the camera more extensively than has heretofore been conceded.

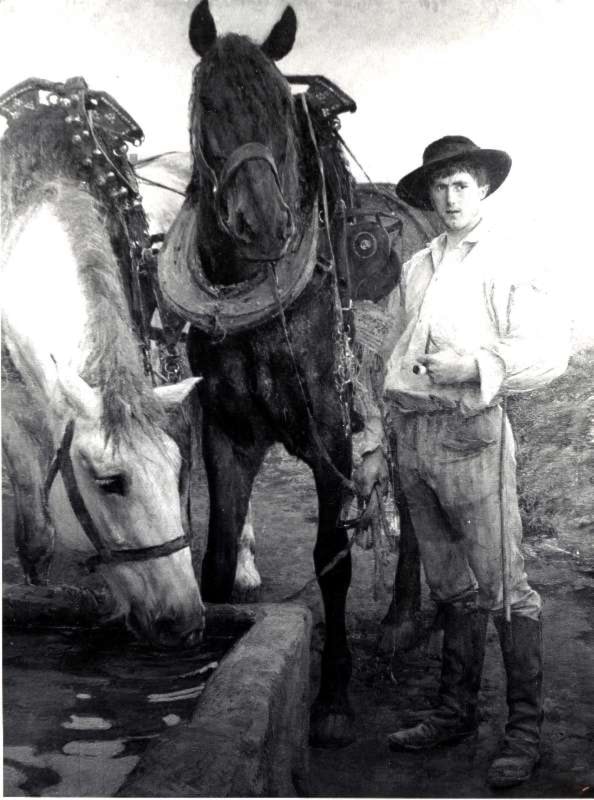

Here ... there are some artists of rare ability, of extreme sincerity, who are astonishing observers, far more conscientious than one can imagine, who spent enormous amounts of time and who lavish superior talent to give us just the emotion which might be produced by photography. M. Dagnan-Bouveret is one of these artists...and his Horses at the Watering Trough can just as well serve for our demonstration.

If the critic for Le Siecle had had further insight into the actual creation of P.A.J. Dagnan-Bouveret's imposing Horses at the Watering Trough it has not been passed down to us.

However, by singling out Dagnan's canvas for particular commendation, and by emphasizing how close the painter had come to a photographic effect, it was possible to sense that Dagnan had completed a work which was somehow different from his earlier Salon entries, and which placed him at the forefront of the "modern" painters of 1885.

The composition also marks, in effect, a change in the painter's development, Dagnan now entered into a complex relationship with the photographic medium since it gave him an opportunity to distance himself from what he was actually painting, providing him with new sources of composition and serving as aide-memoires when his studio models could no longer pose for him. Allusiveness toward photography permeates all of his mature work but is nowhere more apparent than in three key paintings which afforded much acclaim when displayed at the Paris Salons of the mid-1880s. These canvases, which we will treat individually later, are Horses at the Watering Trough, The Pardon in Brittany and Breton Women at a Pardon.

Dagnan's Early Interest in Photography

It is difficult to pinpoint with accuracy, with the evidence now available, the moment when Dagnan-Bouveret first became involved with photography. During his Parisian student days (in the 1870s) Dagnan had come into contact with a number of young painters, including Jules Bastien Lepage , who may have utilized photographs as sources for their paintings. When Dagnan visited Bastien-Lepage's rural village of Damvilliers in the late 1870s, in the company of the American realist painter Julian Alden Weir , he may have had an opportunity to see photographs of Bastien's grandfather, a figure of considerable, a figure of considerable importance in his grandson's early canvases. Similarly, when Dagnan painted several early portraits of his own grandfather, Gabriel Bouveret, he instilled a striking naturalness into the pose and an accuracy into the facial features that was suggestive of a growing awareness of the facility offered by photography in the creation of lifelike images. Dagnan's involvement with photography may have blossomed through contact with his teacher, Jean-Léon Gérôme , at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. Teacher and pupil remained close friends near Vesoul in the Franche-Comte, so that he could be near his former professor who occasionally visited the region.

Since it is now generally acknowledged that Gérôme used photography as an aid for some of his figures and architectural details, Dagnan's interest in the medium could correspondingly have been nurtured through discourse with his mentor and friend.

Whatever the source of his introduction to photography, it is apparent from such canvases as Une Noce chez le Photographe (exhibited at the 1879 Paris Salon) that the medium strongly kindled the artist's imagination. This painting was widely discussed in the daily press. Some critics found it too anecdotal while others applauded Dagnan's originality. The work was photo-engraved by Goupil in April 1880 and circulated in Paris, London, and the Hague. Dagnan's career was now successfully established. Une Noce also intimates that at the moment of his own marriage to Anne-Marie Walter, Dagnan regarded photographs as accurate recordings of a personal event. He was now fully cognizant of the importance of the medium to people at all levels of society and, as an artist, he found its application to his own work inevitable.

If Une Noce chez le Photographe amused some members of the Salon audience with its anecdotal theme, The Accident carried strong narrative overtones, imminently evocative of a naturalist story. Dagnan carefully observed a series of rural types, rendering his figures "with a power and a sincerity (that were) extraordinary." While there is no direct evidence that Dagnan used photographs in the completion of his work, its accurate detail and scrupulous sense of person powerfully suggest it. One critic commented that the secret of Dagnan's success was in the "impersonality" of his draftsmanship: he never emotionalized for effect, even when a sense of drama was present. Every detail in this work, including the precise character of the figures "... was scrupulously copied and executed...to produce an illusion." Dagnan was fastidiously trying to recreate reality, even leading some critics to compare his achievements to those of the earlier Dutch painters.

The Horses at the Watering Trough

Despite Dagnan's active participation at the Salons during the 1880s, it was not until he exhibited his Horses at the Watering Trough that he received the official sanction of the government by the state purchase of his canvas. At the time, Dagnan was classed among a group of young painters who were beginning to immortalize their region of the Franche-Comte by drawing on themes from the daily life of this remote area. The Horses... was highly praised at the Salon as an example of a "grand style," although few would have recognized it as being part of a strong naturalist tradition.

It now appears that since his marriage to Anne-Marie Walter in 1879 Dagnan had spent summers in the Franche-Comte, staying in the rural village of Corre where his wife's father was a reputable mill owner. Indeed, his daughter probably carried a handsome dowry into the marriage.

It is uncertain whether Dagnan's paintings at this time are related to events and personalities in Corre, but it is indisputable that Horses... was prompted by observations of day-to-day village life, made concrete with the assistance of a series of photographs taken locally in 1884.

The preliminary photographs for the canvas identified on the back of each print as "photo d'études pour 'les chevaux d'Abreuvoir'," indicate that similar to some other painters of the period, Dagnan used several photos to create a composite image on his canvas. An exact reproduction of the horses' stance was transferred to the canvas, most likely through the use of a squared photograph, tracing paper, and the utilization of a grid measurement pattern. However, there are some significant alterations. The white horse has been cropped by the edge of the canvas; the brown horse has been partially obscured by the watering trough in the foreground.

The horses were photographed in an interior courtyard with a single figure, M. Walter, holding the animals' reins. In the completed painting Dagnan developed his scene against an expansive landscape and replaced the well-dressed M. Walter with a field laborer who had just brought the horses to a watering trough at the close of the day, creating the illusion that these horses were directly related to field work-despite the fact that they are obviously not quarter horses. Rather, they are more delicate animals who were employed in pulling M. Walter's carriage through the countryside. Thus, Dagnan carefully altered reality to suit his own artistic purpose.

For the finished Salon paintings, however, no evidence exists to indicate whether Dagnan made use of photographs when the substitution of the field laborer became an integral part of the painting. It's possible that Dagnan, in order to create the appearance of peasant life in the Franche-Comte, also resorted to the use of a studio model to create the pose and to wear the costume of his adopted region. With this full assimilation of photographic devices, Dagnan brought his painting into line with the innovative tendencies of some of his contemporaries, thereby heightening his naturalist flare and drawing the attention of a Salon audience eager for new insight into French rural life.

The First Brittany Pardon

No other area of France excited as much interest during the late 1880s as Brittany. Numerous painters visited the Brittany isthmus; many studied the culture of the region and recorded the religious ceremonies that had remained unchanged for centuries. Among these devotional processions were the mystical Brittany pardons where peasants in traditional garments participated in a religious ritual that occurred in different locales.

Dagnan-Bouveret visited Brittany in 1886 to gather first-hand information in preparation for his first Brittany theme: The Pardon in Brittany. In a letter to his friend Henri Amic in September, 1886, Dagnan mentioned his recent return from Brittany, suggesting that he may have been in the north at the time of the regional festivals. By late October 1886, in another letter to Amic, he wrote that he had spent eight days on his "Breton" composition, revealing that the first Brittany scene, exhibited at the 1887 Salon, was completed in the small rural village of Ormoy, in the Franche-Comte.

A photograph showing Dagnan at work on The Pardon in Brittany reveals that the artist completed the painting outside his home in Ormoy, working from models he dressed in Brittany costumes. Each of the figures was carefully posed, placed in the precise location demanded by the recreation of the religious procession and then photographed so that Dagnan would have a record of his models for later reference. It can be seen that the models were drawn from Dagnan's immediate circle since the young woman, third in the procession, was his wife Anne-Marie. She was photographed at another moment, casually chatting with her husband during an interval in the painting session.

The Second Brittany Composition

With the success of the Pardon behind him, in 1887 Dagnan began a second Brittany scene by focusing on Breton Women at a Pardon. Utilizing documentary photographs taken at Rumengol, Brittany, during his trip in 1886, Dagnan plotted his canvas. He regarded both of these photos as "études," preliminary studies, much like the first stage in the preparation of an academic painting. They sustained his awareness of the atmosphere of Brittany as well as providing him with the detail needed for completion of the background church and the group of figures. The second photograph, which contained a seated figure in the foreground and a standing male at the left, may have inspired the final organization of the composition.

A series of photographs taken at Ormoy in 1887 shows that Dagnan posed a group of Franche-Comte peasants in a field to help visualize his patient assembly of women. Although he left the position of the figures at the left of the photograph unaltered, Dagnan continually modified the figures at the right. Indeed, the second photograph already squared for transfer, shows how he inserted a new figure and pose into the final arrangement. Despite these changes, and others that Dagnan made, the positioning in the final painting of the two young women at the right is not the same as found in the existing photographic sources. Since a drawing, utilizing tracing paper, exists for the young woman at the right, it is possible that Dagnan may have relied on other, as yet undiscovered, photographic sources for this canvas

The location of a photograph showing Dagnan working in his atelier also provides clues to his working method. Tacked on the rear wall of his studio, in preparation for he completion of the final grouping of figures for Breton Women at a Pardon, are several sheets of tracing paper cut into irregular shapes. Each tracing paper fragment has been interrelated with another as Dagnan manipulated his figures in this manner to achieve his finished composition. Since the small ledge at the rear also contains a photographic print of some posed models, the photo of Dagnan at work reveals other information. Dagnan is seen in the process of squaring a photo for transfer since he is holding in his fingers a mechanical measuring device.

For this painting, Dagnan had depended more exclusively on photographic illusion. The preliminary images can be seen as aide-memoires; the other, secondary photos of models and tracings are a painstaking elaboration upon these. The final composition, although completed in 1887, was not exhibited until the 1889 Salon.

The exhibit evoked a similar critical reaction to that of his earlier Brittany scene, with much commentary as to how Dagnan had captured the "... soul of Brittany." Paul Mantz was more enthusiastic, noting that Dagnan-Bouveret had emerged as the major painter at the Salon. The critic was enflamed by Dagnan's ability to associate contemporary reality with overtures of past ages through his selection of the Brittany pardon theme.

He linked his canvas, through its delicacy of execution, with the masters of illuminated manuscripts of the fifteenth century.

Once again, through the use of photography, Dagnan had created a complex image of Brittany while painting in his makeshift outdoor studio in Ormoy. By manipulating techniques he had learned from colleagues, and by mastering the intricacies of composite scenes, he had become a foremost transcriber of naturalist illusion. In effect, he worked as an early photo-realist, constantly checking his photographic aids against either the actual model (as he could be doing in his Ormoy studio) or his own personal vision of his work. The sophistication of his compositions and the ease with which he integrated photo-mechanical means with his own style were characteristic of the fully mature artist.

If it's now apparent that Dagnan relied heavily on photography, it is less obvious why he pursued this course. Dagnan was one of several naturalist painters who reacted to the continually expanding interest in recording man in his environment in an accurate way. This intention may lie at the heart of Dagnan's methods. Since he can never be regarded as an avant-garde artist, his reliance on photographic illusion raises other crucial issues that will eventually have to be resolved. Since Dagnan succumbed to the lure of the new medium, it's quite likely that other academically trained artists followed suit. What is most compelling in Dagnan's case is that he ran the gamut of known photographic experimentation, thus revealing that it was not only

The Impressionists who saw the benefits of the new medium but also the conservative painters who were dedicated to exhibiting at the government-sponsored Salons and later at those held by the Societe Nationale des Beaux-Arts (after 1890).

Thus, Dagnan's use of photography can now be viewed as a new phase in the medium's impact on artists in several camps. It removes part of the cloak of secrecy that has plagued a full understanding of the interrelationships between painting and photography in the last decades of the nineteenth century.