From Homer to the Harem

WITH THE ADVENT OF MODERNISM, those masters who carried the great traditions of academic art into the 19th century, like Gérôme and Cabanel , were pushed into the background, and their work fell into oblivion. A principal objective of the Dahesh Museum of Art is to rediscover and renew the public's appreciation of these fascinating figures.

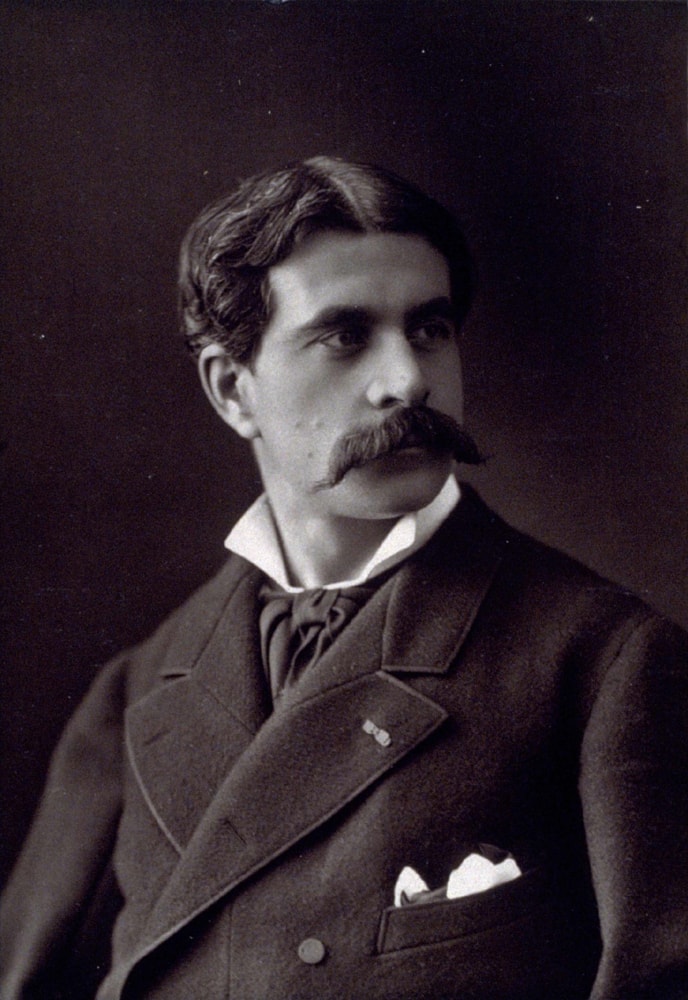

It is thus with pride and excitement that the DMA presents the first retrospective of Lecomte du Nouÿ (1842-1923), a painter who remained true to the aesthetic values, formal principles, and highly developed skills of his academic training throughout a long and prolific career.

In his own lifetime, Lecomte du Nouÿ's work was admired and disparaged, but rarely ignored. As the critic Edmond Haraucourt wrote: "... no one passes indifferently by his canvases; they impose a respect and a vague restlessness that emanate from things with which one communicates uneasily, things that one only penetrates after long study."

In his own lifetime, Lecomte du Nouÿ's work was admired and disparaged, but rarely ignored. As the critic Edmond Haraucourt wrote: "... no one passes indifferently by his canvases; they impose a respect and a vague restlessness that emanate from things with which one communicates uneasily, things that one only penetrates after long study."

Lecomte du Nouÿ's oeuvre, as represented by the 100 paintings, drawings, and oil sketches in this exhibition, covers the conventional academic spectrum of portraiture, history and the classical past, travel (with an emphasis on exotic locales), and religion, with a strong narrative focus on the human form. Yet while laboring in these well-cultivated vineyards, this artist often threw in an idiosyncratic twist - an erotic, even transgressive charge that might account in part for the "restlessness" noted by his contemporaries. This freighted edge is sure to provoke interest in our own time.

Heretofore, modern-day viewers have had no choice but to withhold judgment on Lecomte du Nouÿ: many of his paintings were lost to war and history, and few of those that do survive are on display in public collections. Little has been written about him since his death in 1923. In assembling this exhibition, curator Roger Diederen has performed an invaluable service to scholarship and to that part of the art-loving public eager to expand their horizons.

The Evolution of an Artist

There is little documentation - few letters, personal papers, or even anecdotes - to flesh out the particulars of Lecomte du Nouÿ's life. The standard, but rare biography (Guy de Montgailhard's Lecomte du Nouÿ, Paris, 1906), is essential but not always reliable. Still, the basic facts of his early artistic life are clear.

Born in Paris, Jean Lecomte du Nouÿ started drawing early, reportedly inspired by visits to a nearby zoo. At the age of six he made portraits of his father and uncle. In 1861, the 19-year-old artist enrolled in the Paris atelier of Charles Gleyre (1806 - 74), an artist whose pedagogical approach was remarkably free from doctrine: he stressed the importance of individual style, rather than slavish adherence to an established school.His strong reputation as a teacher with independent views accordingly attracted an impressive cadre of students ranging from future Impressionists to fledgling academicians. Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-70) and Alfred Sisley (1839-99) attended Gleyre's atelier, in fact, at roughly the same time as Lecomte du Nouÿ.

On view here, 43 Portraits of Painters from Charles Gleyre's Atelier (ca. 1856-68) contains portraits, by diverse hands, of artists who studied at the studio during this period. Lecomte du Nouÿ may be the second man from the left in the middle row.

Gleyre's background might well have appealed to this artist on other grounds: he had traveled extensively in the Near East, including a two-year sojourn through Greece, Turkey, Rhodes, Egypt, and the Sudan that yielded many drawings and watercolors of people and places. Lecomte du Nouÿ, whose most successful later works evoked Orientalist themes, might even then have been attracted to the exotic qualities of Gleyre's imagery.

Gleyre's tutelage is apparent in the first of Lecomte du Nouÿ's paintings to be exhibited at the Paris Salon, Paolo and Francesca (1863), completed shortly after he left Gleyre's atelier.

Of Lecomte du Nouÿ's brief stay with his second teacher, Emile Signol, relatively little of note is recorded. It was in this studio, however, that a fellow student encouraged him to read Le Roman de la Momie (The Novel of the Mummy), Théophile Gautier's 1856 historical novel about an enamored pharaoh which became the inspiration for many of his later paintings. Gautier's narrative style, which applied meticulous, scholarly descriptions to exotic fantasy, prefigured similar qualities that would appear in the painter's work.

Lecomte du Nouÿ's next and last teacher was the most important, the great Gérôme (1824-1904). Gérôme was one of three artists appointed to lead the newly created painting studios at the École des Beaux-Arts in 1864, and Lecomte du Nouÿ was among the first group of 13 in this class.

It was under Gérôme that Lecomte du Nouÿ learned to pursue the academician's goal of depicting la belle nature, the purest and most beautiful representation of natural forms, and began to develop the technical skill he would apply in service of this quest. He acknowledged his debt in no uncertain terms, saying in later life, "Gérôme est mon maitre, et Raphael mon Dieu. (Gérôme is my master, and Raphael my God.)"

For his part, the master apparently thought highly of his pupil. According to an 1866 letter from the director of the École, the sculptor Eugène Guillaume (1822-1905), "Mr. Gérôme considers him one of the students from his atelier on which he can base the highest hopes for the future." Gérôme also expressed his esteem in concrete terms, choosing several of Lecomte du Nouÿ's drawings to be copied in lithographs for the celebrated cours de dessin, a widely used drawing course created by Gérôme and Charles Bargue (and the subject of a recent Dahesh Museum of Art exhibition).

Three of these lithographs are on view in the current exhibition: Horse Head from the West Pediment of the Parthenon, Theseus, and the Belvedere Torso, front view (all ca. 1868).

Gérôme is my master, and Raphael my God.

— Lecomte du Nouÿ

It was with Gérôme's encouragement that Lecomte du Nouÿ made the first of many journeys abroad, visiting Egypt with painter Felix Clèment (1826 - 88), in 1865.Two paintings from that year, on display here, document that journey: The Great Pyramids and Night Scene in Kaphira, near Gizeh, Egypt.

A painting from the end of Lecomte du Nouÿ’s student years vividly dramatizes the painter's position vis a vis the competing forces in art of his day, and the degree to which he had internalized academic principles. According to his biographer and friend, Guy de Montgailhard, a fellow student (and unidentified pupil of Gustave Courbet ) had challenged Lecomte du Nou to paint a simple nude following realistic principles, i.e., mere observation of nature. The resulting work, The Charmer (ca. 1870, presented at the Salon that year), was a meticulously finished study informed by ideals of composition and proportion, and embellished with such conventional references to antiquity as a double flute, animal skin, and staff.

During the years of Lecomte du Nouÿ’s study with his three teachers, he began to explore the artistic themes that would dominate his entire career, and which are presented in this exhibition: classical motifs, portraits, scenes inspired by his travels, particularly to North Africa and the Middle East, biblical subjects, and history.

Classicism

In his depiction of subjects from classical myth and literature, Lecomte du Nouÿ followed the tenets of the néo-grec (new Greek) movement, whose pioneers included both Charles Gleyre and, most importantly, Jean - Léon Gérôme, one of its foremost exponents.

These painters, radical in their heyday of the late 1840s and 1850s, redefined the treatment of historical and mythical subjects, shifting narrative emphasis from didactic evocations of universal truth (as exemplified in the work of Jacques-Louis David [1748-1825]) towards vignettes of individual experience. In this they followed the lead of the Troubadour painters, who in the 1820s and 1830s had depicted the world of the Middle Ages and Renaissance through informal, personalized stories. Gérôme's Cock Fight (1847), widely held to epitomize the first flowering of the néo-grec movement, is seen here in a photograph.

The first of Lecomte du Nouÿ's assays in this genre, The Greek Sentinel (seen here in an 1865 engraving after an untraced painting of the same composition), evokes a passage from Aeschylus’s Oresteia trilogy, in which a watchman laments his endless task of vigilance for the signal that Troy has fallen. It was completed with the encouragement of three friends who agreed to pose for the arms, hands, and draperies of the painting, to spare the young artist the expense of a model.

A year later, The Invocation of Neptune (1866) was awarded a gold medal at the Paris Salon, exempting all of Lecomte du Nouÿ's later submissions from juried scrutiny. This picture, a family sacrificing to the sea god to ensure the safe return of a loved one, was inspired by the Homeric Hymns. It drew high praise from the great critic and exponent of l'art pour l'art, Théophile Gautier: "There is nothing to equal the mysterious solemnity of this antique scene," he wrote. "Mr. Lecomte du Nouÿ has a rare, deep feeling for the Antique. Although the small size of The Invocation of Neptune will mean that it will escape the attention of the crowd, it is nevertheless one of the most serious of the Salon."

Given the painting's size and arresting features, it is unlikely that Eros (1873) escaped anyone's attention. The enormous figure, described by the critic Dubosc de Pesquidoux as "a beautiful pink-toned boy with lascivious eyes" is surrounded by putti with butterfly wings, and caskets of jewels. Lecomte du Nouÿ's highly evocative treatment of this mythological theme was inspired by a small ancient gemstone.

In The Mendicant Homer (photogravure after an 1875 painting, which has been lost), the artist offers an image of the great poet, blind, destitute, reciting his verses and playing a lyre to eke out a living as he wanders from town to town. An actual classical sculpture, a bust of the blind Homer that Lecomte du Nouÿ must have known from the copy in the ancient sculpture department at the Louvre, obviously influenced the facial features. A conventional reading of this legendary tableau sees the shepherd boy who guides the bard as the genius of poetry, in an allegory of inspiration. But the details emphasized by Lecomte du Nouÿ's néo-grec interpretation invite the viewer to contemplate the very personal fact of Homer's poverty.

Portraiture

As it had for countless artists before and since, portraiture offered Lecomte du Nouÿ both a commercially lucrative genre and an opportunity to practice painterly skill, here in pursuit of the academic beau idéal.

In the portraits that Lecomte du Nouÿ made in the course of his long career, he shows the influence of his teacher Gérôme as well as, more distantly, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867). This is particularly evident in Mrs. Eglantine Pujol (1869); her image, with its elegant but unostentatious dress, is a typical representation of a 19th-century bourgeoise. The influence of Ingres is clear in the pose, while the technique and palette are indebted to Gérôme. In his later portraits, Lecomte du Nouÿ inclined more toward the model of his teacher.

Adolphe Crémieux (1878) is of particular biographical interest, in that the sitter, a famous Jewish statesman, was the grandfather of Lecomte du Nouÿ’s first wife. The bronze statuette of the Greek orator Demosthenes, standing on the mantle beside the imposing figure of Isaac Adolphe Crémieux (1796-1880), is apt in view of Crémieux’s passionate involvement in such political issues of his day as the separation of Church and State, free compulsory public education, and general amnesty for those involved in the Paris Commune. The law that gave French nationality to Jews in Algeria bears his name.

The Catholic, conservative Lecomte du Nouÿ could be assumed to share few of these Republican principles. Yet his marriage to a Jewish woman, Valentine Peigné-Crémieux (1855-1876), and his continuing connection with her prominent family - at a time when anti-Semitism was rife in France - suggest a broader-minded, more complex personality.

Scenes from Travel

Lecomte du Nouÿ shared the wanderlust of many of his contemporaries. Although his visits to the East clearly provided the richest lode of artistic material, his scenes from France and elsewhere in Europe have their own charm.

Venice, a frequent destination, was the subject of several large Salon paintings. His numerous oil sketches convey a more relaxed, personal appreciation of one of his favorite cities. Four of them are on exhibit here. Venice, Seen from the Public Garden, and two entitled Venice, the Quarter of San Giovanni i Paolo, date from an 1873 visit. View of Venice with an Apparition (undated), with its image of a woman in the sky above the city, brings a dream-like touch more typical of Lecomte du Nouÿ's Orientalist works.

View of the Carpathian Mountains (1897) was painted during a stay in Bucharest, where Lecomte Nouÿ stopped en route to Constantinople to visit his brother André, newly appointed architect to the Romanian royal family. This long stopover yielded more than landscapes: an introduction by his brother to the royal family resulted in several portrait commissions, one of which, in Studies for State Portraits of King Charles I and Queen Elizabeth of Romania (ca. 1895), is represented here.

Orientalism

Also in common with his contemporaries, Lecomte du Nouÿ displayed in his work a fascination with the Near and Middle East which led to his most celebrated paintings.

Contemporary commentators have subjected such Orientalism to an intensely critical re-evaluation, reducing it, in the extreme case, to an expression of imperialism, racism, and sexism. A more value-neutral reading might propose that, to the sensibility of a 19th-century European such as Lecomte du Nouÿ, representations of these lands, their inhabitants, and unfamiliar customs were driven by a benign curiosity that allowed the projection of personal ideas and fantasies

Lecomte du Nouÿ's Orientalist paintings, in particular, embody the paradoxical melding of historicist, representational accuracy, informed by first-hand experience of these places, and a liberated imagination unmatched in his treatment of other themes. The eroticism, violence, and drug-induced hallucination prominent in these works, for all the discipline of their technique, suggest an unlikely affinity between this academician and such exemplars of 19th-century décadence as the poet Charles Baudelaire.

Lecomte du Nouÿ's most famous painting, The Bearers of Bad Tidings, now lost but represented here by a photograph, is based on an episode in Gautier's Le Roman de la Momie. It depicts an Egyptian pharaoh, his despotic fury spent, surrounded by the bodies of the messengers he has slain. Critic Jules Claretie compared Lecomte du Nouÿ's brooding ruler to an Osirian statue, the corpses to "bronze sculptures lying on the ground," and the composition as a whole to an opera backdrop. (This last comparison is highly relevant to the Dahesh's most recent exhibition, Staging the Orient: Visions of the East at La Scala and The Metropolitan Opera.)

The Bearers of Bad Tidings was a huge success, attracting crowds at the 1872 Paris Salon. It was widely reproduced, and firmly established the young artist's reputation. Its wide and lasting fame is attested by a political caricature that appeared in The Bystander, a British periodical, nearly a half century later: Sid Treeby's Bearers of Evil Tidings (November 19, 1913).

The White Slave (1888) also achieved great renown, gracing the cover of a contemporary edition of Victor Hugo's Les Orientales and Gerard de Nerval's Voyage en Orient. The subject, one of the Georgian or Circassian concubines who on the basis of race was most highly prized in the Ottoman Empire, is rendered as an opulent object of consumption. The luxurious fabrics and succulent foods that surround her, the abstracted expression with which she contemplates the plumes of smoke curving upward from her lips, and her opaline, nearly boneless body present an impossible dream of leisure and pleasure. Although the composition is clearly indebted to the odalisques of Ingres and Gérôme, its sultry, seductive radiance bears an idiosyncratic stamp.

In The Dream of a Eunuch (1874), the unattainable fantasy of sexual fulfillment becomes a nightmare. This painting is based on the reference, in Montesquieu's fictive Persian Letters (1721), to the eunuch Cosrou's desire to marry the concubine Zelide. Against the distant, moonlit backdrop of the mosque of Sultan, Cosrou reclines on a terrace, apparently stupified by opium or hashish, as the pale blue smoke from his long-stemmed chibouk materializes into the dancing Zelide, who wears only a teasing smile. Just above the lovely apparition floats an Oriental putto whose conventional bow and arrow have been replaced by a bloody knife and barber's bowl, emblems of Cosrou's mutilation and impotence.

Religion

Church commissions were particularly desirable to an artist like Lecomte du Nouÿ, in light of his unreconstructed academic reverence for the heft and loftiness of large-scale work. Intense competition surrounded these scarce, lucrative assignments, so the commission to paint two altarpieces for the enormous Eglise de la Sainte-Trinité, constructed in Paris in 1861-67, was something of a coup.

The paintings that he executed for the chapel dedicated to Saint Vincent de Paul (1576/80-1660) remain in situ and are represented here by photographs, as well as several compositional sketches and detail studies.

Saint Vincent de Paul Bringing the Galley Slaves to the Faith (1876) reflects the saint's care for convicts who, before embarkation or when ill, were confined in miserable dungeons. He converted many to Catholicism, and established a hospital for them.

Saint Vincent de Paul Helping the Inhabitants of Lorraine After the War of 1637 (1879) refers to the saint's charitable work in eastern France after the Thirty Years War. To Lecomte du Nouÿ's contemporary audience, the allusion to Prussia's occupation of Lorraine, ongoing since 1870, was unavoidable.

In such works as At the Tomb of the Virgin, Jerusalem (1871) and the larger reworking of the same theme, Christian Women at the Tomb of the Virgin (1877), Lecomte du Nouÿ gave religious themes an Orientalist touch. The distinctive rendition of the devotees' garments, the accurate depiction of the church's arched doorway, and the wide view of the nearby Mount of Olives suggest that the painter may have actually visited the Holy Land.

The Bible and Orient come together in Judith (1875). This painting depicts in profile the head of a Middle Eastern woman whose exotic costume features the shatweh, a traditional headdress worn by married women from Bethlehem.

Non-Christian people practicing their faith were another staple of Orientalist art. One or more visits to Morocco may have suggested to Lecomte du Nouÿ the setting and subject of Rabbis Commenting on the Bible on Saturday (1882), and also The Marabout Prophet Sidna Aissa, Morocco (1883). Lecomte du Nouÿ's personal experience abroad was probably responsible for his meticulous attention to costume and architectural detail in the latter work.

History

For all his accomplishment in other genres, Lecomte du Nouÿ carried to the end of his career a desire to be recognized as a history painter in the grand academic tradition. But beyond the fact of a dwindling market for such works, particularly works on the customary large scale, a fundamental shift in values and historical appropriateness had taken place.

The controversy surrounding Dying for the Fatherland (1892) conveys some of the difficulty Lecomte du Nouÿ encountered in maintaining his classical academic posture in a world that had moved on. The painting was criticized for its cold, mythological style, as well as the questionable propriety of depicting a modern soldier lying naked on the battlefield; the artist replied that his goal was to represent not one soldier, but all who had died defending their country.

An early photograph of this painting shows a battle in the background between combatants wearing recognizably 19th-century uniforms in an apparent reference to the Franco-Prussian War two decades earlier. It was later replaced by a generic landscape; Lecomte du Nouÿ responded to the criticism, it appears, by repositioning his subject in a timeless context.